Last time, I was thinking about how a collective imagination can bond humans. This time, I’m wondering how we can extend that bond beyond the human race.

At the moment, a lot of people are asking about what machines might become: how will we relate to them in the future? What sort of issues might we need to address in 50, 70, 100 years time? It’s a fun game, and important of course, but I think we’d do well to pull focus back to the present sometimes.

That in mind, I’ve been considering the possibility that machines are already like us.

Even now, in digitally primitive 2017, technology can offer a safe way to explore our experiences of Otherness. In this time of global divisiveness and alienation, machines have the potential to help us see the common experiences between very different sorts of entities. They can be a helpful reminder that we’re not special (or, if we are, then everything is).

Not only does technology give us a way to rehearse our interactions with and feelings about Others, it also suggests a path towards a kind of empathy of the physical – a theoretical bond that might be shared between everything that draws energy, and dares to vibrate in the world.

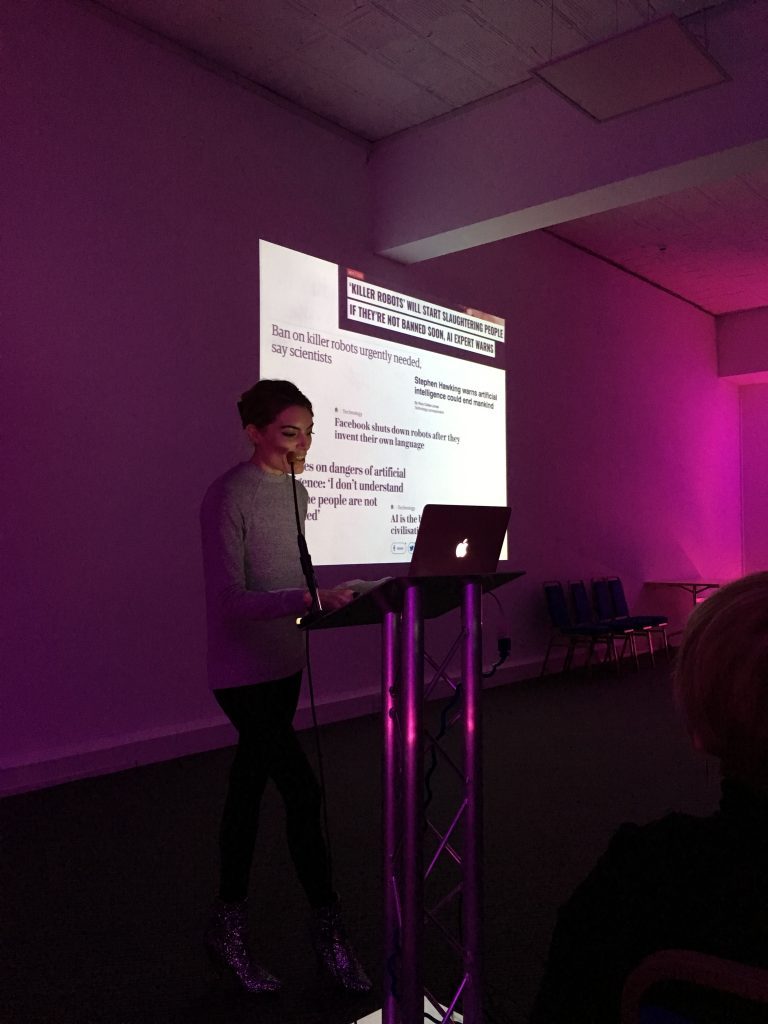

This is the language of dance, in a way, and is one place where dance and tech might find common ground. It’s also a positive alternative to the apocalyptic stories the media feeds us about advancing tech –because this is a zombie story really. An empty-eyed Other rises suddenly from some sunken place, closing in on us from every angle, after our jobs, our power, our privacy, and any sense of control we thought we had over our lives. Why are zombies so particularly repulsive? Because they’re made of us – they remind us of what’s coming to all of us, the one certain future. Just as robotic people are somewhat horrible, and just as CGI creatures are “an insult to life itself”, the most unsettling visions aim for our distant future and land in our mortal one. Like so many things, the fear of AI seems to be about mortality. Once again, we are with the Panaceans on this.

I believe it goes beyond the uncanny valley. Our worries about AI aren’t just instinctual disgust about things that seem a bit-human-but-not. I think they might be an aversion to things that seem human on the surface, but hint at a supernatural experience of time. It’s not just the standard fear of what we don’t understand, it’s the fear of creating something we don’t understand; something that can supercede us in our sense of time and space – that can leave our realm and operate on us mysteriously.

I ran an event last week about “AI and Creativity” and the question of time came up. Why do computers have to be so fast that they’re totally out of step with humans? Perhaps this dissonance is part of what we find so unsettling – only a monster or a deity could move at such speed! What might a ‘slow AI movement’ look like?

One reason I was keen to create an “AI that watches television” out of the Pixy camera was to take the sting out of the popular AI conversation and slow everything down to a human pace, by showing this positive “kindred physicality” of all beings. There’s a level at which a camera inside a mechanical skeleton, instructed to follow certain colours, is doing exactly the same thing as a human who’s been given the same instruction. Computers aren’t particularly like brains, but physical stuff is like physical stuff, and light and movement in a moment of time are simply what, and when, they are.

This is partly why I like working with light and motion. They are honest, physical things with needs like ours (a bit of space, a bit of time, and someone to notice). They are us too, whether you believe we’re made of light or stars, or just plain old energy.

But back to the work. It’s been more of a thinking than a making week. The big AI event I curated for Site triggered some really interesting chats with experts in different fields. In addition to the stuff mentioned in this post, I’ve started to ponder some apocalyptic imagery around floods. Who would survive the floods, when they certainly come? Only the water-dwellers and the birds, for whom it need not be a disaster. What’s the opposite of the eruptive apocalypse – what might be the antidote for it? Perhaps only total submergence, a restoration through original fluid, whether we came from the sea or just a womb. Again, I seem to find myself falling in step with Octavia’s lot. The fires are very final, but as long as we are passengers in water, we represent a moment before choice, and there’s still hope.

The livestream I mentioned last time is currently running off my laptop and very much in R&D mode, so probably not actually live when you click on it, unless you get very lucky. There are some recordings of test runs like this one that you can check out in the meantime, though.

I’ve also had a digital print of my latest designs done in simple cotton, and was really pleased by how well the colours came out, not to mention the very pleasing one-pixel-to-one-stitch resolution. I thought about the fabrics in the Panaceans’ buildings: the upholstery and the healing squares, but especially the napkins and tablecloths on the laid, but empty tables in the dining room. An empty table setting is a terribly poignant thing, whether you’re waiting for a soldier who will never come home, or an Archbishop who won’t return your phone calls.

Next steps: more graphics – probably relating to fluid healing and the ‘silver lining’ of watery apocalypses, a fancier “crow module”, a more satisfactory livestream set-up, and a development in the fabric idea.