Messiaen and the End of Time

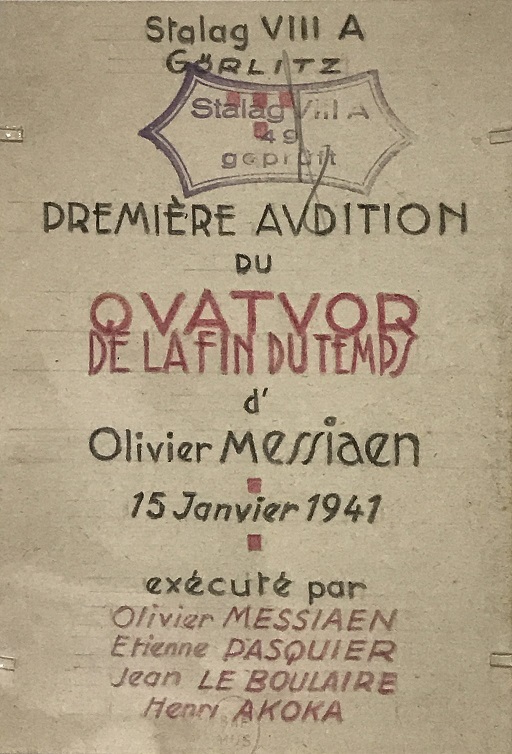

A new recording of Olivier Messiaen’s “Quatuor Pour la Fin du Temps” (Quartet for the End of Time) was released during the summer by OUR Recordings – performed by Christina Åstrand (violin), Per Salo (piano), Johnny Teyssier (clarinet), and Henrik Dam Thomsen (cello). Messiaen (1908-1992) composed the quartet in 1940 while captive in a German prisoner-of-war camp in Silesia. The piece had its first performance (as "Quatuor de la Fin du Temps") in January 1941 to an audience of French, Polish and Belgian prisoners of war.

Messiaen learned piano as a child and studied at the Paris Conservatory before working as the organist at the Church of Sainte-Trinité in Paris and teaching at the École Normale de Musique and the Schola Cantorum. In 1939, he had enlisted in the French Army, however he was captured when France fell in June 1940 and imprisoned in Stalag VIII-A. As a composer, he was given access to writing materials in the camp, and he played the piano for the first performance of the Quartet, with three other prisoners (Jean Le Boulaire (violin), Êtienne Pasquier (cello), and Henry Akoka (clarinet)). He was returned to France, and Paris, under German occupation in 1942 where he taught at the Conservatory and continued to compose.

In the preface to the printed score (1941, in French), Messiaen says the quartet was “directly inspired” by the opening verses of Revelation 10. The full text, in its King James translation, is as follows:

And I saw another mighty angel come down from heaven, clothed with a cloud: and a rainbow was upon his head, and his face was as it were the sun, and his feet as pillars of fire: And he had in his hand a little book open: and he set his right foot upon the sea, and his left foot on the earth, And cried with a loud voice, as when a lion roareth: and when he had cried, seven thunders uttered their voices. And when the seven thunders had uttered their voices, I was about to write: and I heard a voice from heaven saying unto me, Seal up those things which the seven thunders uttered, and write them not. And the angel which I saw stand upon the sea and upon the earth lifted up his hand to heaven, And sware by him that liveth for ever and ever, who created heaven, and the things that therein are, and the earth, and the things that therein are, and the sea, and the things which are therein, that there should be time no longer. But in the days of the voice of the seventh angel, when he shall begin to sound, the mystery of God should be finished, as he hath declared to his servants the prophets. (KJV Revelation 10:1-7.)

The biblical passage printed in the preface (apparently taken from the (1843) Bible de Tours with minor modifications) includes verses 1-7 (omitting parts of the second and sixth verses, and all of the third and fourth). The printed text includes the phrase "Il n'y aura plus de temps" (in verse 6) which can be rendered "there shall be time no longer" in English. The “time no longer” formula reflects an older tradition of translation for the passage (based on the Greek χρόνος/chronos/time); the word "delay" (or references to "waiting" in simplified versions) are more common in place of "time" in more recent translations of the passage. For example, the New International Version (1978) and the New Revised Standard (1989) give the phrase as "There will be no more delay", and the Contemporary English Version (1991) has “The angel said, ‘You won't have to wait any longer…’” So, in relation to this verse, the Bible de Tours is closer to the sense of the Wycliffe Bible ("time shall no more be") or the King James ("there should be time no longer") than to more recent variants. Amongst well-known French translations, after the Bible de Tours in 1843, which was reissued in a successful illustrated version in 1866, there was an oscillation between “delay” (Perret-Gentil et Rilliet (1869), Bible Annotée de Neuchâtel (1900), Synodale Nouveau Testament et Psaumes (1921)) and “time” versions (Lausanne (1872), Vigouroux (1902), Louis Segond (1910), A. Crampon (1923)). The “delay” formula seems to have become the norm in French translations after Amiot-Tamisier in 1950 – reflecting a sense that, in the words of Ben Witherington III in the New Cambridge Bible Commentary for the book of Revelation (2003), “this phrase chronos should not be interpreted to mean that there will be no more time, as if time was to be dissolved into eternity” (p. 156).

Craig Koester (2014) has identified four of possible translations for the phrase. The first, dating from antiquity, is that “Time itself will end” anticipating a point when “time ceases and people are freed from temporal limitations” (p. 479). Bede (2013), for example, says of the passage that “the changeable variety of the times of this world will cease” (p. 178). Koester observes that “internal thematic connections make it preferable to relate the angel’s words to the issue of perceived delay in God’s action” - however, he notes that it is nonetheless the case that “Revelation does culminate with an end to temporal existence” (p. 480, emphasis added). The second variant is that “there will be no more delay in fulfilling God’s purposes” - though Koester notes that in Revelation “the end does not come. The announcement of the kingdom is delayed” (p. 480, emphasis added). The third and fourth variants are more modest references to the time for repentance coming to an end, and assurance that the waiting period will end (p. 480). (Koester’s preference is for the latter.) Messiaen’s interpretation of the passage is at odds, then, with standard contemporary interpretations. He is perhaps closer to Bede, and to Aquinas’s reference to Revelation 10:6 in the Summa Theologiae (Suppl. Qu 84.3): “time which is the measure of the heaven’s movement will be no more” (although, time will exist in another form “resulting from the before and after in any kind of movement”).

As a devout French Catholic in the 1940s, we might expect Messiaen to be more familiar with the older sense of the phrase, and indeed with the Bible de Tours translation of the Vulgate – which, in any case, appears to be the version cited in his preface. It is worth noting, however, a meaningful difference in emphasis between the title of the work and the language of its inspiration. The title (“End of Time”) hints at a sense of a cataclysmic change, closer to notions of the “end of the world” of much contemporary and popular thought reflecting ideas of apocalypse as the cataclysmic disruption of human affairs. The wording of Revelation 10:6 used by Messiaen suggests, as we have seen, something more metaphysical (“there shall be time no longer”): the suspension of the human experience of time passing in the perpetuity of the divine eternal.

In the preface, Messiaen says the Quartet's "musical language is essentially transcendental, spiritual, catholic" and that a “tonal ubiquity” of the melody and harmony brings the listener into “the eternity of space or time". He explains the eight movements of the piece as reflecting six days of creation, the seventh day of rest, and the eighth as the prolonging of the sabbath rest into "the unfailing light and unalterable peace” of eternity. In Messiaen’s music, this is not, then, the end of the waiting period before the arrival of God's kingdom or arrangements for its arrival implied in modern translations, nor the extinction of time and being in a nihilistic sense suggested by some strands of 20th century apocalypticism associated with nuclear or anthropocene threats, but the end of the movement of time itself in an older, spiritualized sense: the endless changelessness of divine being. Thus, Messiaen's Quartet hints at the achievement of perfect divine peace, not the collapse of all values we might expect to find in the composition of a man held in captivity by the Nazi war machine.

In the general article on Apocalypticism in the Critical Dictionary of Apocalyptic and Millenarian Movements we identified a recent evolution in the use of the term Apocalypse from “ideas of the revelation of transcendent or divine truth” towards “general and cataclysmic change in human life and culture”. Messiaen’s dual reference is perhaps indicative of a mindset moving between the two: the title tending towards ideas of cataclysmic change in human life, and the musical expression aspiring towards the articulation of divine truth. Peter Gutman (2018) has discussed the ways the title of the piece can be taken musically and literally: “Messaien sought to end our accepted notions of musical time”, and refers to Messiaen’s study of ancient Greek music and the 13th century Indian treatise on rhythm, the Sangitaratnakara – both of which challenge Western ideas of rhythm in music and are reflected in the Quartet. In this case, the only adequate theological account of Messaien’s ideas about the end of time may be the music itself.

References

Aquinas, Thomas. (1920.) Summa Theologiae: Supplementum Tertiae Partis. New Advent Catholic Encyclopaedia. (From The Summa Theologiae of St Thomas Aquinas. 2nd edn rev. 1920.) Accessed 21 Sep 2022. https://www.newadvent.org/summa/5.htm.

Bede. 2013. Commentary on Revelation. Faith Wallis (trans.). Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Gutman, Peter. 2018. ‘Classical Notes: Olivier Messiaen: Quatuor pour la fin du Temps: Quartet for the End of Time’. Retrieved 22 Sep 2022. http://classicalnotes.net/classics6/quatuor.html.

Koester, Craig R. 2014. Revelation: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Messiaen, Olivier. 1941. ‘Préface d’Olivier Messiaen au Quatuor pour la fin du temps’. Retrieved 22 Sep 2022. http://www.petraglio.com/Clarinet/Agenda_files/messiaen.pdf.

Witherington III, Ben. 2003. Revelation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Alastair Lockhart is CenSAMM Academic Co-Director and a Fellow of Hughes Hall in the University of Cambridge. He has research interests in 20th century religious change, the psychology of religion, and 1914-1945 in particular. www.divinity.cam.ac.uk/directory/lockhart