Ancient Jewish and Christian Apocalypticism

When we read the Apocalypse of John (also known as the Book of Revelation), we encounter what might be termed “classic” Christian apocalyptic thought. The prophetic seer, John, has a heavenly vision, mediated to him by Jesus Christ in the guise of a sacrificial lamb; the vision reveals what will happen at the end times when God decides to intervene in human affairs. Within the visions, we encounter numerous fantastic beasts that symbolize all manner of evil people and entities, followed by a series of violent punishments for the unrighteous and an illustrious spectacle of a pristine, cosmic Jerusalem reserved for the righteous. The Apocalypse of John is part of a wider genre of ancient Jewish apocalypticism, which is typically characterized by (1) a rigidly dualistic worldview (good versus evil, insiders versus outsiders, righteous versus unrighteous, and the like), (2) inherent pessimism about the state of humanity, (3) hope that divine intervention will happen soon, and (4) expectation of rewards for the righteous and punishment for the unrighteous. While Jesus tends to feature prominently in Christian apocalyptic texts, we regularly find in Jewish apocalypses characters like the Son of Man or messianic figures that are not understood to be connected to Jesus at all.

But when we consider the terrain of all ancient Christian texts, especially ones composed before the Apocalypse of John, it is striking that some of them depict Jesus as an apocalyptic prophet only in a limited sense, and some, not at all. Though it is likely true that most early followers of Jesus held apocalyptic beliefs of some sort, they didn’t all find it necessary to deploy these ideas within every text they composed about Jesus. In what follows, we will consider the apocalyptic contours of perhaps the earliest collection of sayings and stories associated with Jesus.

The Enigmatic Q Source

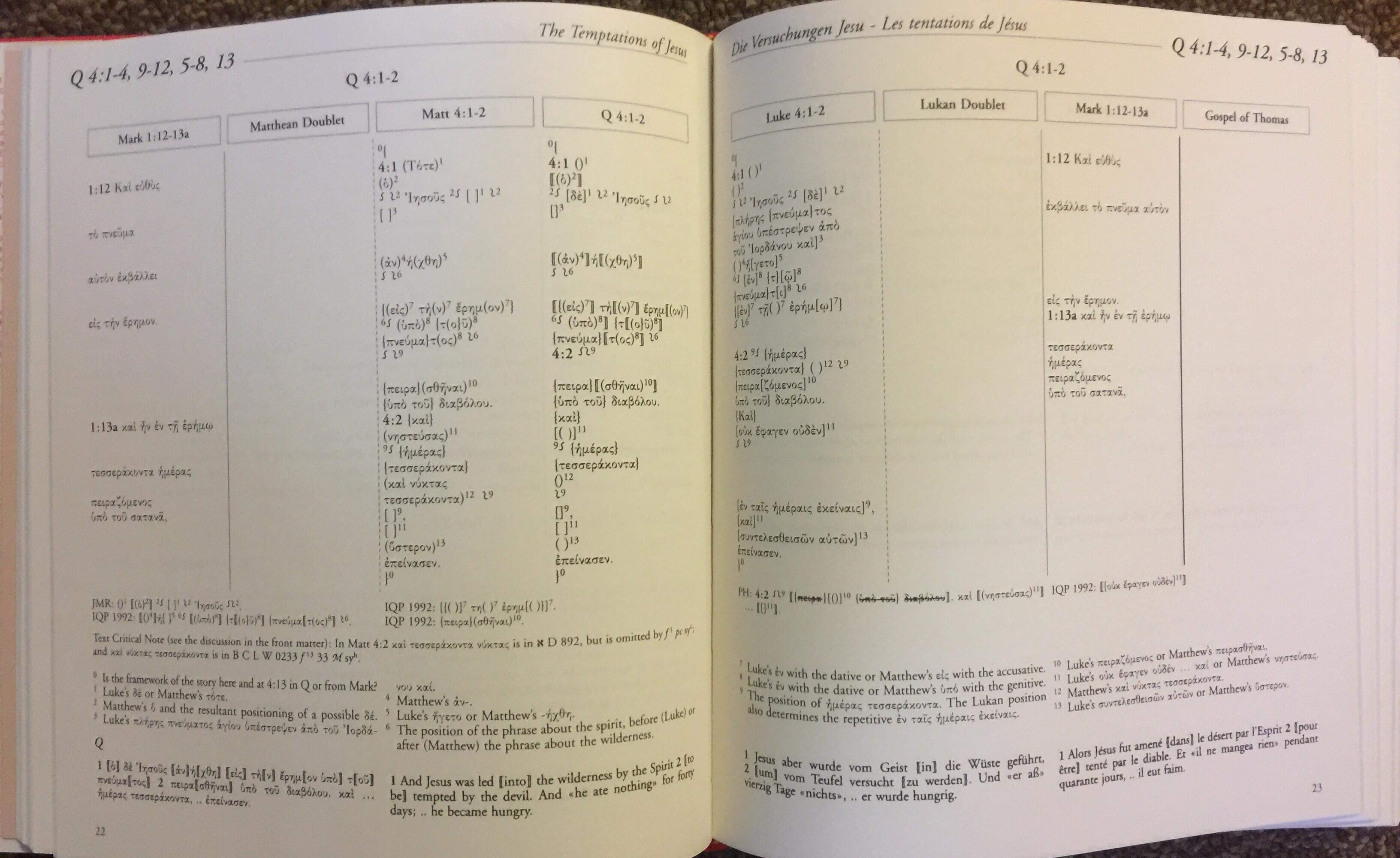

The earliest collection of traditions connected to Jesus is known to biblical scholars as Q, which is an abbreviation of the German term Quelle, meaning source. Essentially, Q is a hypothetical source that makes sense of the verbatim similarities between the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Luke. Most modern readers fail to see these word-for-word similarities between Matthew and Luke, because they read the gospels sequentially as they are presented in the New Testament. However, when similar passages are placed side by side, the similarities in narrative structure, word order, and vocabulary are striking. Especially when it comes to the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, most biblical scholars agree that there must be some literary relationship among them (that is, they used a common source or used each other for sources). The detailed arguments cannot be explored here, but the most common view is that the Gospel of Mark was the first gospel to be written, and that the authors of Matthew and Luke used Mark’s story as a kind of narrative “backbone” for composing their gospels. “Q” refers to the material that Matthew and Luke have in common that they did not derive from the Gospel of Mark, and importantly they locate Q passages at different points in the Markan narrative, which means neither author was aware of what the other was doing.

Q can be reconstructed from extensive, word-for-word parallels in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. An international group of scholars worked collaboratively on this reconstruction in the 1990s and produced The Critical Edition of Q. Despite some minor disagreement among scholars, this publication represents more or less what this hypothetical document is argued to have looked like. Once reconstructed, it becomes clear that Q was primarily a list of sayings of Jesus: witty one-liners, wise observations, enigmatic parables, and ethical pronouncements. Moreover, it contains some of the most famous teachings attributed to Jesus, such as the Sermon on the Mount and the woes against the Pharisees. Importantly, Q does not contain a story of Jesus’ death (though it would be absurd to assume that the author[s] were unaware of it). Rather, Jesus is mainly important as a teaching figure and as a prophet sent by God to reform “this generation”/the people of Israel. Thus, we can look toward Q for a glimpse of what the earliest followers of Jesus wanted to say about their revered teacher and their own experiences in the world. And when it comes to apocalyptic thought, we can see just how valuable of an intellectual resource apocalyptic ideas were.

Apocalypticism in Q

The extent to which Q reflects apocalyptic thought is debated. Q is not a formal apocalypse, in terms of genre, nor does it contain a specific divine revelation. Because Q, as a source for the gospel narratives about Jesus, might be the closest text to the time of the historical Jesus, the stakes are high: does the earliest source remember Jesus as an apocalyptic preacher or not?

The simple answer is yes. In the reconstruction of Q, there are many sayings that presuppose an apocalyptic timetable. The vantage point of the document appears to be situated between the time of Jesus’ life and the future coming of the Son of Man (an apocalyptic figure derived from the Book of Daniel that Christians came to identity with Jesus). According to Q, the Son of Man’s return is imminent, though the exact time is impossible calculate. Moreover, his swift return will be accompanied with acts of violence and force. For instance, in Q 12:39-40, Jesus compares the coming of the Son of Man to a violent home invasion by a robber: “But know this: If the householder had known in which watch the robber was coming, he would not have let his house be dug into. You also must be ready, for the Son of Man is coming at an hour you do not expect.” The parable following this warning in Q likens the return of the Son of Man to a householder who returns from a trip to find his slaves disobeying his orders. In a remarkable passage that highlights the violent judgment involved in the coming apocalypse, Jesus explains, “The master of that slave will come on a day he does not expect and at an hour he does not know and will cut him to pieces and give him an inheritance with the faithless.” Q underscores that this dramatic, violent return will be initiated in the midst of seemingly ordinary circumstances. In Q 17:26-30 Jesus compares the situation to the time of Noah: “As it took place in the days of Noah, so will it be in the day of the Son of Man. For as in those days‚ they were eating and drinking, marrying and giving in marriage, until the day Noah entered the ark and the flood came and took them all. So will it also be on the day the Son of Man is revealed.”

Q also includes enough details so that we can envision what rewards and punishments are awaiting different groups of people when Jesus returns as the Son of Man. John the Baptist, also known for his apocalyptic preaching during the first century, is featured early in Q (3:7-9, 16-17) with some of the most vivid descriptions of how apocalyptic judgment will play out:

[John] said to the crowds coming to be baptized: Snakes’ litter! Who warned you to run from the impending rage? So bear fruit worthy of repentance, and do not presume to tell yourselves: We have as forefather Abraham! For I tell you: God can produce children for Abraham right out of these rocks! And the ax[e] already lies at the root of the trees. So every tree not bearing healthy fruit is to be chopped down and thrown on the fire. …I baptize you in‚ water, but the one to come after me is more powerful than I, whose sandals I am not fit to take off. He will baptize you in holy spirit and fire. His pitchfork is in his hand, and he will clear his threshing floor and gather the wheat into his granary, but the chaff he will burn on a fire that can never be put out.

Jesus himself never states anything so violent in Q, but he does affirm that apocalyptic judgment will involve a severe separation of different groups. “I tell you,” Q’s Jesus predicts in Q 17:34-35, “there will be two in the field; one is taken and one is left. Two women will be grinding at the mill; one is taken and one is left.”

For the righteous, on the other hand, there are rewards envisioned in the forms of an eschatological banquet and the restoration of an idealized form of Israel. Q 13:28-29 extols the many who will “recline with Abraham and Isaac and Jacob in the kingdom of God” while others are “thrown out into the outer darkness.” Those worthy of election who have followed him, Jesus states, “will sit on thrones judging the twelve tribes of Israel” (Q 22:28-30).

The more complicated answer to the question “does Q remember Jesus as an apocalyptic preacher?” involves considering that only some of the sayings in Q reflect this apocalyptic mentality. Many others do not, and since some of those non-apocalyptic sayings were woven into other ancient texts (such as the Gospel of Thomas, which is nearly devoid of apocalyptic motifs), it is reasonable to conclude that there were many early followers of Jesus who were uninterested in depicting him as an apocalyptic preacher. Moreover, to make matters even more complicated, some scholars have tried to identify which sayings were written first in Q; that is, they have tried to reconstruct the text’s compositional history. After doing so, it seems like apocalyptic ideas were not the earliest material in Q to be penned; rather, the pessimistic, judgmental, apocalyptic sayings appear to have been added later, possibly to reflect on the lack of success of the Jesus movement. In other words, the apocalyptic sayings serve a particular function in the Q: they predict apocalyptic judgment for the people who don’t receive Jesus and his followers favorably. This hostility and combativeness might not have been evident at the beginning of the Jesus movement, but it became more and more common as Jesus and his followers experienced resistance and rejection.

Conclusion

Apocalyptic ideas are no doubt underdeveloped in Q. It is not until the composition of the Apocalypse of John that we see a full-fledged depiction of Jesus as a divine, apocalyptic warrior, leading the armies of heaven against the forces of darkness. In Q, we nevertheless see coherent, albeit nascent, apocalyptic beliefs. Q clearly looked forward to the imminent return of the Jesus as the Son of Man and expected that a definitive enactment of divine justice would accompany this future moment.

Sarah Rollens is Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Rhodes College (USA), and author of Framing Social Criticism in the Jesus Movement: The Ideological Project in the Sayings Gospel Q (Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2014)

The purpose of this and other blog posts is to provide an opportunity for researchers to reflect on and raise discussion points about their research and current issues. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of CenSAMM, the Panacea Charitable Trust, or any other organization. The blog post is made available for non-commercial purposes, if you wish to copy and redistribute the blog you may do so without making changes, and you must credit the author and the source (censamm.org). If you wish to make commercial use of this post and its contents, please contact the author directly. Additional information about the terms of use for the website is available at censamm.org/terms.