When Columbus was discovered on a Caribbean beach, he might as well have carried a placard announcing the end of the world. What is feted as the “new world” from European perspectives is predicated on the end of previous Indigenous worlds.

Similar ruptures occurred as Europeans unsettled the rest of the globe. These are not metaphors or exaggerations.

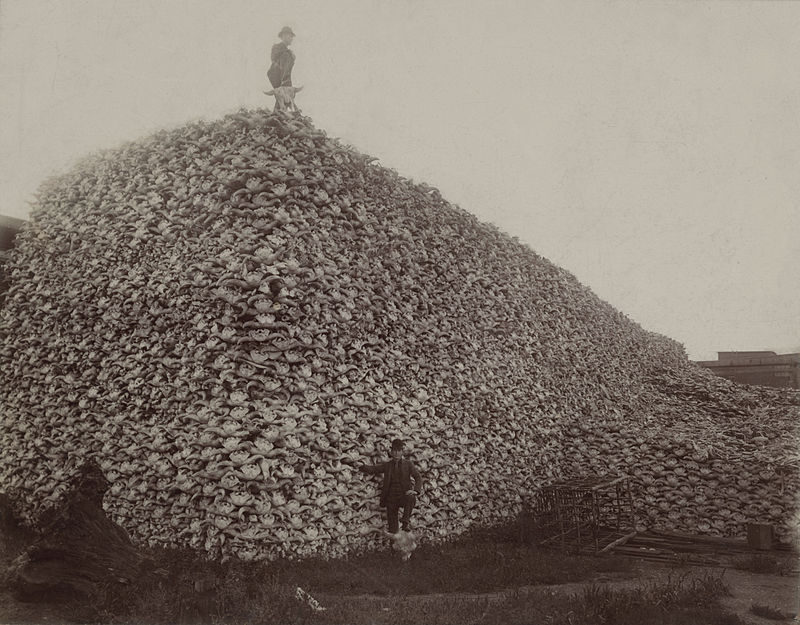

Ecologies of belonging and being that had been productive and lively for thousands of years ended swiftly under the impact of genocide, slavery and other facets of European colonisation. The end of ways of moving through and acting among the larger-than-human communities that are the lands or countries of Indigenous populations (human and otherwise) were ended. Not by accident but with a wilful and thought-through energy. The slaughter of millions of bison in the high plains of North America not only ended the lives of bison and those who hunted them for food, clothing and construction--it also ended the world of a buffalo shaped and sustained ecology.

It was undertaken not only to destroy Native American livelihoods and lifeways but also to re-make the world in the shape of European style farms. This is an example. One among many.

Global climate change might be an unintended consequence of the Industrial Revolution and the pursuit of capitalism and its consumerism. But it is not unanticipated or accidental. It is already ending worlds. The worlds in which there are islands in the Pacific. The worlds in which there are cities by present day coasts. Global consumerism is a world in which there is an “away” to which it is possible to throw plastic. In the world of oceanic currents, there is nowhere to “throw away” waste, it all goes somewhere.

Often it goes into the guts of creatures who then die. Worlds end.

Larry Gross’ book Anishinaabe Ways of Knowing and Being (Routledge, 2014) discusses the post-traumatic stress suffered by generations of Indigenous people following the end of their worlds in North America. But he also presents a compelling view of the resources “traditional” cultures provide for re-making worlds in which there can still be respectful interactions between humans and the larger-than-human community.

The work of another Indigenous scholar, Kyle Whyte, “focuses on the problems and possibilities Indigenous peoples face regarding climate change, environmental justice, and food sovereignty”. He notes that many Indigenous people have already been through catastrophic climate change. This is not vaguely “anthropogenic” but specifically instigated by Europeans who had abandoned their “homelands” and were taking other places.

The forced removal of forest dwelling Indigenous communities (with both genocidal and ecocidal effects) exemplify those climatic changes. Whyte’s work does not dwell on the eras of past world-ending. It is concerned with enhancing the resources of Indigenous communities as the current global climate crisis aggravates existing inequalities and inequities. It is about the re-making of ecologies of dwelling with justice.

Two of the building blocks of the world made by and for colonial settlers and capitalist consumers (i.e. most of us today) are the ideas that “nature” and “culture” label separate (separable) realms and the related notion that humans are distinct from other life-forms on earth. Rejecting such assumptions is a pre-requisite for making a world in which many species might survive or even thrive. This is not going to be an easy task. Climate change, oceanic acidification, rising sea levels, polar melting, carbon and methane atmospheric heating, radiation pollution and other results of global industrialization will unmake this world.

Listening to narratives alternative to those of “Western modernity” may generate knowledges and provoke practices that might enable the composing of a world in which the larger-than-human community of all living beings finds ways to live justly. Seeking ways to participate (responsibly and with respect) in ways of being and moving among that larger-than-human community may inspire new or refreshed world-making possibilities.

I find myself inspired at Indigenous led cultural festivals to think that fusions of ceremonies and entertainment, along with dramatic acts and restrained listening, might at least help us find ways to mitigate the changes now occurring. I recognise that these changes are apocalyptic both by being destructive and by revealing another world emerging.

Graham Harvey is Professor of Religious Studies at the Open University, and author of Animism: Respecting the Living World (Hurst, 2nd edition 2017). This blog is a version of his presentation (“Between trauma and justice: Indigenous knowledges of Climate Change”) to the CenSAMM “Climate and Apocalypse” conference.